The End of an Era

Posted: July 17, 2017 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Big Magic, Cheryl Strayed, Eat Pray Love, Elizabeth Gilbert, Fiddler on the Roof, Hook Em Horns, Magic Lessons, New York Times bestseller, podcast, Project Repat, Sunrise Sunset, Texas A&M, University of Houston, University of Texas, Wild 9 CommentsHey there, it’s been a while! Countless times in the last several months I’ve thought, “I really want to write something for my blog” and yet….Life gets in the way. Big time. But here I am, so let’s get to it.

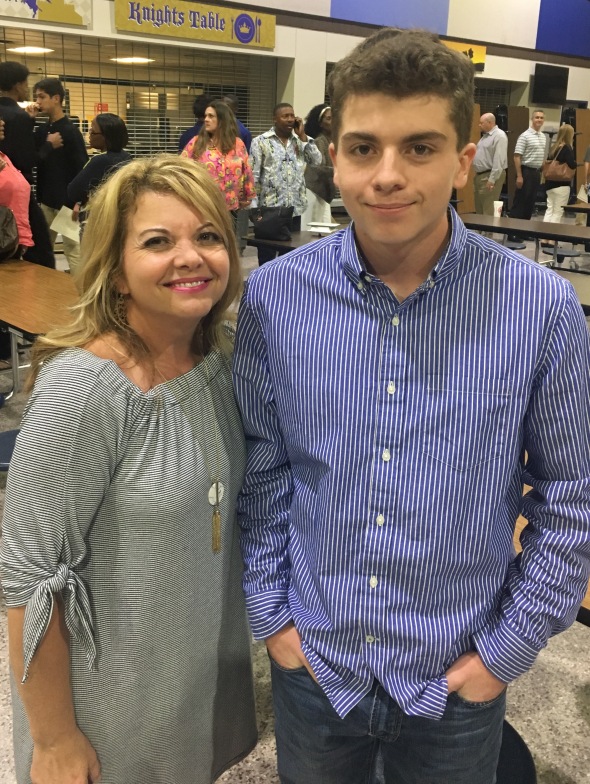

It’s been busy around here, with my firstborn graduating from high school and preparing for college. Lots of changes in the last couple of months, and lots more to come. In April, my boy played his last baseball game. In May, he turned 18 and went to prom. In June, he graduated high school. In August he will leave for college.

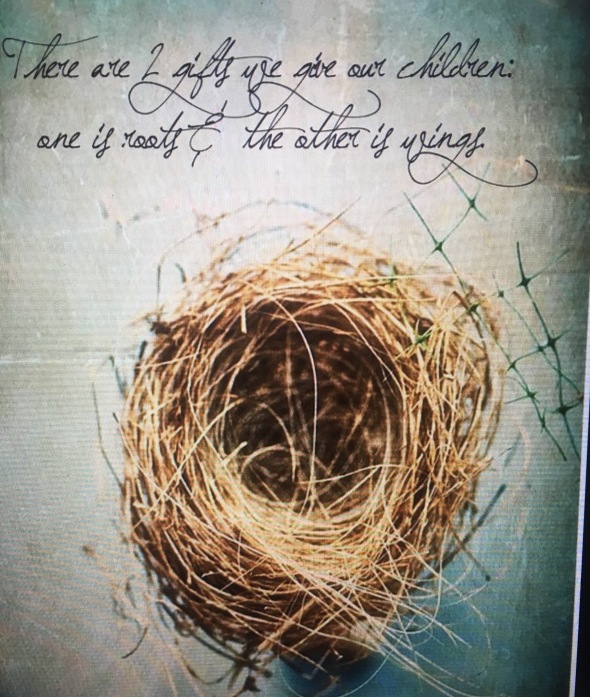

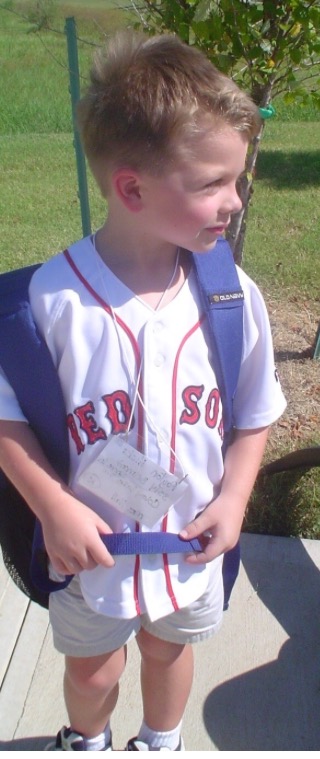

I suppose I’m joining the ranks of parents around the world who wonder: wasn’t it just the other day that my kid started kindergarten? Wasn’t it just last week that my sweet little boy wore a paper tag around his neck with his name and bus number? At the risk of sounding like Tevye in Fiddler on the Roof, wasn’t it yesterday when he was small???

It goes without saying that I am proud of this kid. Although he received a scholarship to the University of Houston, he chose Texas A&M University (the hubs and I both try not to wince or whimper about the fact that our son will wear maroon instead of our beloved burnt orange).

Time is a funny thing: moving glacially slowly in some cases, yet zipping by at warp speed in other cases. I’d heard many times the sage advice to “savor every minute” of my firstborn’s senior year, and despite my best effort, those minutes slipped by and disappeared. We celebrated P’s senior-year milestones and I reminded myself to be present, to drink it all in rather than getting bogged down by the long list of things to do.

The Spring Sports Banquet was a bittersweet milestone: the pride in P’s winning the MVP Award was tinged with a wee bit of sadness that his baseball career was winding down.

Something tells me that once he leaves for college next month, I’ll be looking at this photo rather often. Baseball has been a huge part of our life. Season after season, we savored the wins and mourned the losses, and we watched this boy become a young man.

Baseball has been a huge part of our life. Season after season, we savored the wins and mourned the losses, and we watched this boy become a young man.

On the last home game each season, our school tradition is to honor the senior players in a post-game ceremony, in which the seniors and their families take the field and the announcer reads a letter from the parents to their son and then we present the boys with a keepsake bat. This year, P’s team was locked in a duel for a championship slot, and sadly the Knights fell short and lost the playoff bid (hence his long face after the Senior ceremony).

On the last home game each season, our school tradition is to honor the senior players in a post-game ceremony, in which the seniors and their families take the field and the announcer reads a letter from the parents to their son and then we present the boys with a keepsake bat. This year, P’s team was locked in a duel for a championship slot, and sadly the Knights fell short and lost the playoff bid (hence his long face after the Senior ceremony).

First season of Little League

I’m really going to miss the sweet sound of a bat connecting with the ball. We have spent an awful lot of time in the stands cheering him on (and I spent an awful lot of time pacing the grounds during especially close games). This boy learned to hit a pitched ball at age two and never stopped swinging. Baseball was his first true love, and I suspect the game will always hold a special place in his heart.

We didn’t mourn the end of baseball too long, because shortly thereafter it was time for prom! What is it about boys in tuxedos and girls in evening gowns that is so captivating? As senior year winds down and prom night finally arrives, the juxtaposition becomes apparent: the excitement of what lies ahead, coupled with the memories of the last four years.

Right on the heels of prom was the graduation ceremony and party, a blur of activity and a house full of the people who mean the most to us. So much activity that we failed to take many photos (perhaps the sign of a truly good party — we had so much fun we didn’t even think about taking pictures!).

One of the highlights: this blanket made from his Little League shirts. I like the idea of him taking all those memories with him to college.

My boy was a week shy of turning 10 when I was diagnosed. Double digits for him, a double mastectomy for me.  Eighteen years ago, with the birth of this kid, I went from a being a regular person to being a mother. Eighteen years seems like enough time to prepare for the end of an era. And yet, it’s just not. I’m a believer in the notion that kids leaving home means parents have done their job. However, as it is with many things, it’s easy to be a believer before that notion becomes a reality. The tricky part is remaining a believer as one faces the end of an era.

Eighteen years ago, with the birth of this kid, I went from a being a regular person to being a mother. Eighteen years seems like enough time to prepare for the end of an era. And yet, it’s just not. I’m a believer in the notion that kids leaving home means parents have done their job. However, as it is with many things, it’s easy to be a believer before that notion becomes a reality. The tricky part is remaining a believer as one faces the end of an era.

Swiftly fly the years.

Home Is (bleeping) Burning

Posted: December 7, 2016 Filed under: cancer fatigue, literature, Uncategorized | Tags: ALS, Audible, audio books, caring for a sick parent, Dan Marshall, Home is Burning, Lou Gehrig's Disease, memoir, Mormons, parents with ALS, parents with cancer, parents with terminal diseases, Salt Lake City, Utah 4 CommentsI heard an interview a while back with Dan Marshall, who wrote a memoir about caring for his terminally ill parents. Yes, you read that right: parents, plural. Both of Marshall’s parents had a terminal disease: his mom’s lymphoma and his dad’s ALS.

amazon.com

The book, Home is (bleeping) Burning, tells the story of the Marshall family, who (except for their copious and creative cussing) sound like a regular American family living their lives and doing their thing until their regular lives are upended by health crises. Here’s how Amazon describes it:

For the Marshalls, laughter is the best medicine. Especially when combined with alcohol, pain pills, excessive cursing, sexual escapades, actual medicine, and more alcohol.

Meet Dan Marshall. 25, good job, great girlfriend, and living the dream life in sunny Los Angeles without a care in the world. Until his mother calls. And he ignores it, as you usually do when Mom calls. Then she calls again. And again.

Dan thought things were going great at home. But it turns out his mom’s cancer, which she had battled throughout his childhood with tenacity and a mouth foul enough to make a sailor blush, is back. And to add insult to injury, his loving father has been diagnosed with ALS.

Sayonara L.A., Dan is headed home to Salt Lake City, Utah.

Never has there been a more reluctant family reunion: His older sister is resentful, having stayed closer to home to bear the brunt of their mother’s illness. His younger brother comes to lend a hand, giving up a journalism career and evenings cruising Chicago gay bars. His next younger sister, a sullen teenager, is a rebel with a cause. And his baby sister – through it all – can only think about her beloved dance troop. Dan returns to shouting matches at the dinner table, old flames knocking at the door, and a speech device programmed to help his father communicate that is as crude as the rest of them. But they put their petty differences aside and form Team Terminal, battling their parents’ illnesses as best they can, when not otherwise distracted by the chaos that follows them wherever they go. Not even the family cats escape unscathed.

As Dan steps into his role as caregiver, wheelchair wrangler, and sibling referee, he watches pieces of his previous life slip away, and comes to realize that the further you stretch the ties that bind, the tighter they hold you together.

In the interview, Marshall read passages from his book, and just so you know, the language and some of the topics in Home Is (bleeping) Burning may be less than pleasant for some readers. (Does it mean I’m weird/crude/uncouth/all of the above because I really relate to and enjoy the mom, who is the most prolific with her cussing?). Also note that the Marshalls live in Salt Lake City but are not Mormon, and there are some non-PC comments made about their Mormon neighbors. Perhaps this book is not for the faint of heart. But then again, neither are terminal illnesses or recurrences or sick parents. As Greg Marshall (the author’s brother) so eloquently put it: “For the Marshalls, life is a contest to see who is _____-est. Bravest. Weirdest. Grossest. We take our lack of filter to superlative heights.”

Perhaps my own lack of filter attracted me to the Marshalls’ story. It could also be because I too cared for a sick parent. I too experienced the strange role-reversal that comes with caring for a parent. I write often about the terrible yet honorable practice of becoming the authority figure and advocate for the person who, until their illness took hold, was the authority figure and the advocate for me. I write often about how my mom’s death affected me, and continues to affect me. That’s why my ears perked up when I heard about Dan Marshall and his memoir.

This passage got me. Hit me hard. Reminded me of my own sweet mama (without the cussing). This passage describes the family discussion on Christmas day. The topic is how the family will handle Mom’s lymphoma recurrence and Dad’s new ALS diagnosis. Dan described his mom’s stance upon learning her cancer had come back:

“She wasn’t just going to roll over and let cancer f*** her to death. She was going to fight and fight hard. And she suggested we all do the same.”

Indeed. May we all do the same.

Does It Ever End?

Posted: December 5, 2016 Filed under: breast cancer, cancer fatigue, kids | Tags: biology, breast cancer, breast cancer and young women, cancer, cancer battle, cancer diagnosis, cancer fatigue, cancer journey, cancer recurrence, cancer research, cancer sucks, family, PTSD, real world, schoolproject 7 CommentsOver the weekend, my favorite girl asked me to help her with a project for her biology class. She’s a freshman in high school now. This is what she looked like at age 8 when I was diagnosed with cancer. I took this photo the day before my bilateral mastectomy.  This is my favorite girl today.

This is my favorite girl today.

I know, right??? How does that happen???

Anyhoo, back to the story: my favorite girl is doing a project for her biology class on a disease or disorder that has a chromosomal component. She chose breast cancer.

She needed the basic info of my cancer: stage, treatment, etc., as well as ancillary materials (photos and such) that tell “the story” of her subject’s experience with said disease or disorder. I pulled out my bulging “cancer catch-all” — my binder that holds all my paperwork, like pathology reports. That was easy because it’s all facts: this scan was conducted on this date and found this. Then she asked for the not-so-easy part: details on how my cancer affected me. While there are indeed facts involved with that part too, something else is involved as well, which is what makes it, for me, the not-so-easy part.

Feelings. The dreaded feels.

I don’t like feeling the feels associated with my cancer experience. (I refuse to refer to it as my cancer “journey” because to me that word implies an end point. With cancer, there doesn’t seem to be an end point. I don’t like it, so I’m not gonna use that word.)

Six years out, I don’t think about my cancer experience nearly as much as I used to (hence the loooooooong periods of radio silence from this blog). As with most calamities, time does smooth out the rough edges. But with my favorite girl asking me for all the gory details, that dark period of my life surrounded me, again.

When, exactly, do we “get over” this? At what point does the calamity of cancer lose its potent punch? I’d like an ETA on the return of peace and tranquility. Can someone please tell me when to expect an easing from the powers of the cancer calamity? Because I need to know that at some point, cancer will no longer upend my day like a sucker punch and leave me reeling, wondering why I feel as I’ve been run over by a truck.

That will happen, right?

Even though my cancer experience is no longer the petulant toddler whining for a pack of Skittles in the grocery-store checkout area, apparently that cancer still packs quite a punch. The simple act of flipping through my medical binder to locate information for my girl’s project sent me on a one-way trip through bad memories and scary places. I see myself from a distance, as if I’m watching myself on a screen. In the blink of an eye, I’m no longer a survivor whose scars are a badge of courage. Instead, I’m instantly transported back to that time. Those days. That period.

I hate that cancer has the ability to do this. I hate that cancer still controls me. Like a bad habit or a selfish lover, my cancer has a hold on me. Other people’s cancers have that power over me, too. Like my sweet mama’s cancer. That rat bastard smiles and licks its lips, knowing it is the puppet master and I am the puppet.

I should know better than to expect to be “done” with cancer. After all, I’ve been thinking about it and blogging about it for years. As I wrote early in 2011:

Another things I’ve learned on my “cancer journey” is that someone keeps moving the finish line. I’ve only been at this for 10 months, yet have seen my finish line recede, sidewind, and fade into the distance. It starts even before diagnosis, with the testing that’s done to determine if we do indeed have a problem. Get through those tests, which in my case were a mammogram, an ultrasound or two, and a couple of biopsies. Then there’s the actual diagnosis, and getting through that becomes an emotional obstacle course. Following the diagnosis are lots of research, soul-searching, and decisions. But even when those are through, the real work is only just beginning. After the big decisions come still more testing (MRI, CT scan, PET scan, blood work, another biopsy), and that’s just to get to the point of having surgery. Get through surgery, then through recovery, and just when I think I may be getting “there” I realize that even after recovery, I gotta learn about re-living, which is kinda different when “normal” has flown the coop and there’s a new status quo involved. You might think that finding the new normal would be the end, but guess what? now there’s the maintenance and screening. If you’re the kind of person who makes a list and takes the necessary steps to reach the conclusion, you’re screwed, because there is no end. I can’t even see the goalposts anymore.

I should know damn good and well that there is no end. So why do I keep looking for it?

6 years, plus

Posted: May 3, 2016 Filed under: Uncategorized 21 Comments

mastectomy day, 5.13.2010

Last week marked 6 years since I was diagnosed with breast cancer. I thought about it a few times on the actual day (April 27) but found myself pushing any thought out of my head. Not because I shy away from thoughts of my cancer “journey” — good luck getting out of such thoughts, y’all; anyone who has been down this road or who has watched as someone they know has gone down this road knows that is a futile effort. That’s a very long sentence with a simple idea at its core: if you have been diagnosed with a serious illness, thoughts of that illness come randomly and often.

Personally, I’m in a limbo-like state of wanting to acknowledge the passage of time between D-Day and today, while also not tempting fate. My rational brain knows that recurrence and fate are not intertwined, yet my scardey-cat brain wants to skate far from any potential jinxing.

my babies, 6 years ago

I’m not at all sure what to say or how to feel about 6 years NED (no evidence of disease). I hate to even type that acronym, for fear of unleashing the beast that has already turned my life upside-down and left me permanently changed. I feel like a shit-heel for even mentioning my NED status when so many lovely people (many of whom write stellar blogs) currently have cancer as a recurring character in their lives. I know that could just as easily be my fate, and I know that it still may be my fate.

See, that’s the thing about having had cancer. Regardless of type or stage, once you’ve heard a doctor say some version of “It looks like cancer” you will never be the same. If you happen to be one of those who believe that cancer is a gift, you may want to stop reading right now and head on over to another website — any other website — because I remain resolute in my opinion that if cancer is a gift, I say no thanks.

In reflecting on 6 years post-cancer, I remembered a letter I wrote to my younger self. I need to re-run it, and I need to do that now.

Dear Younger Me,

Listen up, missy: that college dream of yours to light Madison Avenue on fire with clever advertising campaigns isn’t gonna happen. You don’t like the Big City — too many people and way too many germs. That other dream of writing children’s books isn’t going to happen, either. At least not anytime soon. You do end up reading a whole lot of good ones, though, to a couple of precious kids who look so much like your baby pictures it’s scary.

Your smart mouth will get you into a fair amount of trouble. I’d tell you to be careful, go easy, and use restraint, but we both know you’d flip me the bird and keep right on sassing. I can tell you that eventually you do learn the fine art of holding your tongue, but it will never come easy.

That sweet, loyal, smart, cunning and unmatched yellow dog who grips your college-aged heart will never let go. She will protect you, and then your children, for nearly 15 years. She will guard the entrance to the nursery and sleep under the crib. She will show you her back when you get out your suitcase, because she knows you’re leaving, if only for a few days. Her time on this Earth will grow short but she will stick it out longer than anyone expects because she will insist on seeing you through an even rougher patch: the death of your sweet mama.

Guess what, girlie? Your sweet mama keeps a tight grip on your heart, too. Not a day passes without you feeling the loss, in big ways and small ways. (Note to self: don’t give up on trying to make her pie crust. It won’t ever be like hers, but keep trying.)

Just about the time cancer steals your beloved mama, you’ll start getting an annual mammogram. You’re ahead of the schedule thanks to that mama-stealing cancer, and every year the mammogram will come back funky. Don’t settle for the “dense tissue” rationale. There’s a tumor growing, and it ends up taking up a lot of space, both in your body and in your life.

Look, I know you’re going to be busy living your life and raising those two little kids when the diagnosis comes, but please, brace yourself, because it’s going to get ugly fast. And say a little prayer to the environmental-services gods who control your operating room on the day of your mastectomy; maybe we can avoid that post-mastectomy infection that will reorder your life. And BTW, the bilateral mastectomy was totally the right choice. Good girl for following your gut. There will be no hint, not a single whiff, of cancer in your left breast, but it’s there.

Give up right now on thinking your cancer “journey” will be “one and done.” It will be more circuitous than you can ever imagine, and it will change you in ways you won’t discover until years later. Oh, and before you even begin that circuitous journey, you’re going to have to deal with melanoma on your right foot. I know, who puts sunscreen on their feet, right? Hate to tell ya, that even though you catch it early, the surgery to remove the melanoma will be the most painful thing you will experience. Yes, it’s worse than childbirth and a bilateral mastectomy. Oh yeah, about childbirth–when your water breaks, the baby is coming. Yes, he’s early. No, you haven’t finished the birthing class or packed your bag, but it doesn’t matter. And you’re going to get teased for decades for reading ahead in that “What to Expect” book on the toilet in the middle of the night when your water has broken and your much-better-prepared spouse sleeps peacefully, unaware of your foolishness.

It turns out fine, the baby is healthy (but hard-headed). Even the cancer thing is manageable. Not easy, but manageable. I think we both know you can handle it. You’re going to learn a lot, whether you want to or not. Your limits will be tested. You’re going to make some true and life-long friends along the way. You’re going to unload friends, too, in one of many hard-learned lessons. You see, there are people who are willing to give what they want to give, not what you need. This is a very important distinction. Trust me, you’re much happier without ’em. A couple more pieces of advice: first, don’t ignore that knee pain while you’re running. Stretch before and after you pound the pavement. Listen to your body. Pain is its way of saying something is wrong. Ice your knee after each run. I know it’s a hassle, but so is living with constant pain. Years down the road, you’re going to be embarrassed by how you hobble down the stairs like a woman twice your age. You’re going to be frustrated by the ways in which your body fails you. I don’t have an answer for how to deal with that, because I haven’t figured out how to deal with that. I do recommend drinking champagne as often as you can. I don’t have to tell you to never, ever pass up an opportunity to drink some bubbly. The lesson I want you to remember is that the sound of that popping cork will soothe your soul, every time.

Love,

Me

Goodbye, Twenty

Posted: January 10, 2016 Filed under: pets | Tags: 9/11, Dalamatians, FDNY, Fire dogs, firefighters, Ladder 20 company, NYFD, September 11, terrorist attacks, World Trade Center 4 CommentsThe New York City Fire Department suffered a tremendous loss this past week when Twenty the Dalmatian died.

For nearly 15 years, this dog has been a proud member of FDNY. Shortly after the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2oo1, two sherriffs from Rochester, NY, delivered a dalmation puppy to Ladder 20 company. Ladder 20 Company needed a morale boost — the kind that only a puppy can bring — after seven of its members perished on the 35th floor of the World Trade Center’s North Tower.

google images

This beauty served alongside her human counterparts and provided a bit of hope in the dark days that followed 9/11.

barkbox.com

On FDNY’s Facebook page, Lieutenant Gary Iorio wrote about Twenty: “She really helped to build the morale in the years following 9/11. I can’t say enough about what she did to help us. She went on all the runs, she’d jump in the truck, stick her head out the window and bark. She became a local celebrity.”

Dalmatians have been affiliated with fire stations since the 1800s, and I’d venture to guess that none was as beloved as Twenty. Because early fire stations used horse-drawn wagons as fire engines, they also employed Dalmatians. It seems that Dalmatians are able to bond closely with horses, and because horses tend to be afraid of fire, Dalmatians were essential. Early accounts tell of horses being afraid to approach a fire and of Dalmatians distracting and comforting those horses, which allowed the fire wagons to get closer to the fire.

Lieutenant Iorio posted this sweet send-off to his colleague Twenty: “We offer our heartfelt thanks to her for being a loyal companion to FDNY members and the community for nearly 15 years. Today, Twenty has taken her final run to Heaven. Rest in peace, man’s best friend.”

Upon learning of Twenty’s death, FDNYdispatchers transmitted a specific message: 5-5-5-5. The fire code, which has been used in New York fire stations since 1870, signals the death of a firefighter.

5-5-5-5 for Twenty means she has been officially released from duty, and that her job has been done.

RIP, Twenty.

Want more stories of hardworking, hero dogs? Read this.

8 weeks later

Posted: January 3, 2016 Filed under: Surgery | Tags: acupuncture, Cryo Cuff, Graston technique, ice cast, knee replacement surgery, Kneehab XP, myofascial massage, physical therapy, PT, PT after TKR, recovering from knee replacement, total knee replacement, Venapro 21 CommentsFive and a half weeks. 37 days. A milestone — finally. My first real milestone after my knee replacement came on day 37 post-op. On that day, I woke up on my own instead of from pain.

In my last post about my knee replacement surgery, it was easy to imagine constant pain for 6 weeks post-surgery. While I’m happy to have noticed relief a few days shy of that, 37 days is a loooooooooong time to be in pain. And the pain isn’t totally gone, either. As I begin my eighth week with my new knee, I still have pain–especially during and after physical therapy–but it’s no longer my constant companion.

I no longer walk with a limp, thankfully. I can go up stairs with relative ease, but coming down stairs is a different story. My new knee still doesn’t want to bend the way it needs to. It still barks at me and my unrealistic expectations. Even though I had read extensively about recovery and thought I knew what to expect, I had no idea how hard this would be.

If you happen to have a story about a neighbor/parent/spouse/boss who had a knee replacement and “was up and about like normal within a few weeks,” do not tell me about it. Just don’t. I don’t want to know. Yeah, yeah: everyone heals differently, it’s major surgery, anytime they cut your bones it’s a hard recovery blah blah blah. I know that. In my intellectual brain I know that. But in my crazy brain, I have this stupid idea that eight weeks is more than enough time to heal. Crazy Brain and I would like to get back to normal, please.

These days, my life revolves around physical therapy, my ice cast, the Kneehab XP, and a compounded antiinflammatory cream. Three days a week I spend an hour and a half at PT; on the days that I don’t attend PT, I do a series of exercises at home twice a day. Pedaling a stationary bike and doing squats are the least heinous parts of my PT. The Graston treatment falls into the heinous category. Graston involves the therapist using one of these tools to press, scrape, and apply pressure to the injured area. While it can hurt enough to induce a cold sweat and a string of curse words, it breaks up scar tissue adhesions, softens the fascia, and promotes healing.

After the Graston treatment comes acupuncture. Graston breaks up the bad stuff and then acupuncture helps escort that bad stuff away from my knee and out of my system. Here’s hoping that Graston and acupuncture continue to combine WonderTwin powers to heal this mess.

Once I get home from PT, I strap on my ice cast and wait for the cold to overpower the pain. Sweet, sweet relief. This thing is pretty great: the cooler holds ice and water, which flow into the leg cuff, along with air for compression. It gets cold quick and stays cold long enough to wipe out the damage done progress made at PT. If only I could figure out how to store a glass of champagne in the cooler when it’s not strapped to me.

When I’m not icing, I’m firing up the Kneehab XP.  On the inside of this sleeve are electrodes that sit right on top of the affected area and deliver electrical stimulation to the quadriceps to force the muscles to contract. Those quad muscles have been underutilized because of the damage to my knee; by forcing them to engage, the Kneehab XP promotes strengthening and reminds those muscles to get back to work.

On the inside of this sleeve are electrodes that sit right on top of the affected area and deliver electrical stimulation to the quadriceps to force the muscles to contract. Those quad muscles have been underutilized because of the damage to my knee; by forcing them to engage, the Kneehab XP promotes strengthening and reminds those muscles to get back to work.

Here’s how the incision looks today. It too is healing, slowly slowly slowly. Much too slowly for me and Crazy Brain.

TKR = Totally Kraptastic Recovery

Posted: November 26, 2015 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: uusšaauuuu 8 CommentsOn this day of Thanksgiving I would love to be writing about today’s feast. About the recipes I’m trying, or about the traditions we keep alive year after year. Instead, I’m writing about my new knee.

I am 17 days post-op. Seventeen long days. Each of those 17 days so far has challenged me, pushed me, and damn near broken me.

This recovery is hella hard. Crazy hard. No amount of advanced research could have prepared me for how hard this is. The thing that is different about TKR compared to my other surgeries, is that after 17 days, I don’t feel any better. How strange to have spent more than two weeks getting to know my repaired knee without feeling better. Intellectually, I know that I am doing better and am making progress, but I don’t feel it. Every day, my in-home physical therapist measures the angle at which I can bend and flex my repaired knee. Progress is underway, but it is slow going. PT is brutal in all the ways one would imagine: pain, cursing, swelling, cursing, stiffness, cursing. Recovery for a TKR averages in the neighborhood of 12 weeks and can stretch out even longer in terms of making noticeable physical progress. I’ve read many times that the pain from a TKR can last 6 weeks. I can very easily imagine that. So far I’ve had nearly constant pain that is only slightly alleviated by some strong-ass narcotics. Getting used to constant pain requires an attitude adjustment on a whole ‘nother level. I’m still adjusting.

Thankfully, the bruising is mostly gone. The swelling is hanging around, though, and likes to announce its presence each time I take a few steps.

Thankfully, the bruising is mostly gone. The swelling is hanging around, though, and likes to announce its presence each time I take a few steps.

The fleecy sled in the photo above is my CPM (continual passive motion) machine. For two hours at a time, three times a day, my repaired knee gets bent and straightened over and over. After a while it feels like I’m constantly moving, even when I’m not hooked up to the CPM.

This Thanksgiving, my thoughts are not about the feast. When I glance at the clock today, it won’t be related to how long the pie has been in the oven, but about how long it’s been since I had a pain pill. Instead of chopping veggies, I’ll be trying to cut a deal with the universe for some super-fast healing. Rather than slowing down to enjoy the holiday, I’ll be trying to figure out how to make time go faster, so I can be done with this totally kraptastic recovery.

The (nearly) bionic woman

Posted: November 4, 2015 Filed under: Surgery | Tags: bionic knee, carpal tunnel, cubital tunnel, gen pop, post-mastectomy infection, PRP, Synthetic synovial fluid, Synvisc, Tommy John, total knee replacement, ulnar nerve transposition, Wonder Twins 8 CommentsI haven’t written much about surgeries lately. Well, truth be told, I haven’t written much about anything lately. But certainly not about surgeries. Despite the double-digit number of surgeries I have had in the last five years, I don’t like being cut upon or tweaked or refined. I’m good with my rough edges. My body has other ideas, however.

At the beginning of this year I had reached my limit of tolerance for the carpal tunnel pain & suffering so I consulted a well-respected hand specialist and got a nasty surprise. In addition to carpal tunnel, I also had cubital tunnel syndrome (I’m an overachiever that way), so the no-big-deal surgery to correct the issues in my right wrist morped into a full-blown ulnar nerve anterior transposition. It looked like this:

Yuk.

Long story short, the ulnar nerve (which runs from one’s neck to fingertip) becomes dislodged and gets caught on the bony ridge of one’s elbow when one stretches or bends at the elbow. Once dislodged, the nerve needs help getting back in the right place. So, my surgeon had to dig a new channel for my ulnar nerve to lie in, then stitch the nerve into the muscle to ensure that it didn’t go rogue again. It was as pleasant as it sounds (not really pleasant at all). And the scar is about as pretty as you might expect (not really pretty at all). It’s a good conversation piece, though; I’ve been asked more than once if I had Tommy John surgery (do I look like a baseball pitcher?) or whether I won the knife fight.

Now that I am recovered from the fun & games of my arm surgery, it’s time to get back on that OR table and get myself a new knee. Yes, a total knee replacement at the ripe old age of 46.

Don’t be jealous.

I’ve been dancing around the knee issue for years. After two arthroscopies, a lateral release and minor ACL repair, a PRP infusion, and 11 injections of synthetic synovial fluid in the last 10 years, it’s time. The x-rays that show zero cartilage say it’s time. The grinding of bone on bone say it’s time. The uncertainty of being able to get up from a crouched position say it’s time. The increased pain, decreased mobility, and off-the-charts frustration say it’s time.

Sigh.

Big sigh.

I’m not looking forward to this.

That said, I am intrigued by the particulars of an artificial knee; the one I’m getting is cutting-edge. It uses a proprietary Oxinium (oxidized zirconium) on the femoral part of the joint, a PMMA plastic on the tibial side, and a stainless steel piece to add a little sparkle. That oxinium is pretty cool; it’s a metal alloy that once heated transforms into a smooth surface that is super resistant to wear & tear and is much lighter than the metal used in older versions of knee replacement devices. It is free from nickel but will likely still set off the metal detectors at the airport. Fingers crossed that the TSA person who gives me a pat-down is gentle (and cute).

The combo of Oxinium and PMMA plastic are the Wonder Twins of knee replacement devices. Rumor has it this combo can last 30 years. That’s important when one is on the flat end of the bell curve that represents the average age of a knee-replacement recipient. As is my custom, I’m way ahead of my peers in my medical needs. Like 20 years ahead.

Being the weirdo that I am when it comes to surgeries, I like to gather all the gory details about the procedure. I usually watch a youtube video of an actual procedure, too, but usually after I’ve endured the horror of the real thing. Here’s how it will go down: Amy doc will make a vertical incision, probably between 6 and 10 inches, on my bum leg. Once in, he will move my kneecap so he can get to the leg bones. He’s going to cut my femur and tibia (if you’re strangely curious as I am, may I suggest that you don’t google “orthopedic bone saw?” That’s just creepy. The fact that such tools are available for purchase on eBay is even more creepy). He promised to measure twice and cut once. (Because the pieces that comprise an artificial knee come in some 90 sizes, I hope he measures more than twice!) Once the bones are cut, he will shape them to accommodate the new pieces that will make up my bionic knee and will attach the pieces to the bones. Then he will attach the parts to the kneecap, using bone cement. My doc told me that waiting for the cement to dry takes nearly as long as the rest of the procedure. Then he will sew me back up and once I’m awake and somewhat coherent, I’ll be off to my hospital room.

Most patients stay three nights in the hospital, but I’m already hoping to ditch out early. I’ve spent enough nights in the joint. I’m fortunate that my doc has a swanky surgery center not far from my home. There are only 5 rooms, which is good because I have no business mixing and mingling with the gen pop in a regular hospital. I hear a lot of people get really sick in hospitals.

10 years later

Posted: October 13, 2015 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: grief, losing a parent, losing a parent to cancer, missing mom, Motherless Daughters, my mom 17 CommentsTen years ago today, I got the call. The call I’d been dreading. The call from my dad to tell me that my mom was dead. I was in my car, in line to drop my #1 son at school. He was still in the car, but I answered the phone because it was my dad calling. Trying to respond to him while cloaking my words in a way as to not upset my 6-year-old was hard. Living the last 10 years without my mom has been even harder.

I’ve written much about my sweet mama and how much I miss her. I’m not sure that there are new ways to say, I’m sad. I miss her. I feel lost sometimes. I worry that I don’t do enough to keep her memory alive. I can’t believe she’s gone. I don’t want to live the rest of my life without her. I’m afraid I don’t mother my kids as well as she mothered me. I’m totally pissed that she’s gone. I was robbed. She was robbed. It still hurts, a lot. It’s better, but it still hurts.

I miss her. So much.

I’ve been torn today, between wallowing in the sadness and doing the kinds of things she respected. Between feeling sorry for myself and being productive. Between having a shitty day and “walking on the sunny side of the street” (the latter was how she bid me farewell every day when I left for school when I was little). How can I walk on the sunny side of the street when the sunshine is gone?

And yet I will try. I will. Because that’s what she would want.

IDLEs

Posted: September 29, 2015 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: bilateral mastectomy, breast cancer, breast cancer diagnosis, breast cancer research, DCIS, Dr Laura Esserman, IDLEs, National Cancer Institute, Paget Disease 6 CommentsLately, much has been written about the rush-to-mastectomy decisions adopted by women with DCIS diagnoses. DCIS (ductal carcinoma in situ) is the diagnosis given when abnormal cells reside in the milk ducts. It is precancerous and noninvasive. It is not life-threatening, although it can lead to an increased risk of developing an invasive cancer. While it is unquestionably scary to receive such a diagnosis, some in the medical community are questioning whether a slash-and-burn reaction to DCIS is appropriate. The current standard of care for DCIS is surgery and radiation. A natural reaction for a woman with DCIS is to undergo the most far-reaching form of treatment available. I won’t argue with that, because no one has the right to judge another person’s reaction to or decisions toward a cancer diagnosis. Anyone who tries to should be punched in the brain. Repeatedly.

That said, data don’t lie, and the case being made for a less-aggressive approach to DCIS is gaining ground. Dr Laura Esserman, a breast surgeon at the University of California, San Francisco, is setting the pace. In a recent New York Times article, Esserman says her goal is “to move the field and do right by our patients.”

Instead of immediately ordering biopsies for women with unsettling findings on their mammograms, Dr Esserman recommends active surveillance. She favors the “wait and see” approach, speaking out about the myriad ways in which a woman is adversely affected by slash-and-burn treatment for cancers that rarely progress beyond DCIS.

Dr Esserman is bringing to light the fact that mammograms — while valuable — find the slow-growing, non-metastasizing cancers that lead to panic more than they find the most lethal forms of breast cancer. She is lobbying for big changes in the early-detection world and has asked the National Cancer Institute to consider dropping the word “carcinoma” from the DCIS label. Instead, Esserman would like for DCIS to be renamed “indolent lesions of epithelial origin.” IDLE would replace DCIS as the way to describe a stage 0 diagnosis. IDLE is catchy and much friendlier than DCIS, if you ask me.

This woman is turning the breast-cancer world on its head, and I like it. In an era of less face-time with doctors, Dr Esserman spends as much time as needed with each patient, often texting or calling them at home. A big part of her “wait and see” approach to DCIS is asking the patients soul-searching questions and utilizing specific testing to gather further evidence before recommending surgery. She’s pushing for more innovation in clinical trials and for fine-tuning the process of screening for breast cancer. In cases for which she does recommend surgery, Dr Esserman counsels and frets like a family member, and even sings to her patients as they undergo anesthesia. Personally, I’d much prefer a serenade to a prayer before I go under the knife. I can imagine her patients, smiling and relaxed, as they enter the last blissful sleep they will enjoy for a while to come.

I love Dr Esserman. I don’t know her, but I love her. I love that she’s crashing through long-standing views and taking the road less traveled. I believe she will enact great change in the landscape of breast cancer. I wonder how I would have reacted to my own breast cancer diagnosis if mine had lacked an invasive tumor. If my cancer was simply DCIS, would I have chosen a different path? I don’t know, but I do know how scary my diagnosis was. I know that the scorched-earth treatment plan was right for me. I had watched my mom die from cancer at age 67. My kids were still in grade school when “the C word” was applied to me. I wanted to be as aggressive as possible, so my choice was to go balls-out against cancer. And it’s a good thing I did, because my “non-affected” breast turned out to be riddled with cancer. Nothing showed up, though, on any of the screenings. Nothing. When Dr Esserman mentioned that mammograms don’t find the more lethal forms of breast cancer, I nodded my head knowingly and actively talked myself off the roof rather than allowing myself to think “what if?” What if I had chosen a single lumpectomy or single mastectomy, and that smattering of cancer cells and Paget disease in my “unaffected” breast had continued to evade detection? Would I be sitting here, typing this post? Would I be glancing up from my computer to see this guy outside my window?  What if?

What if?